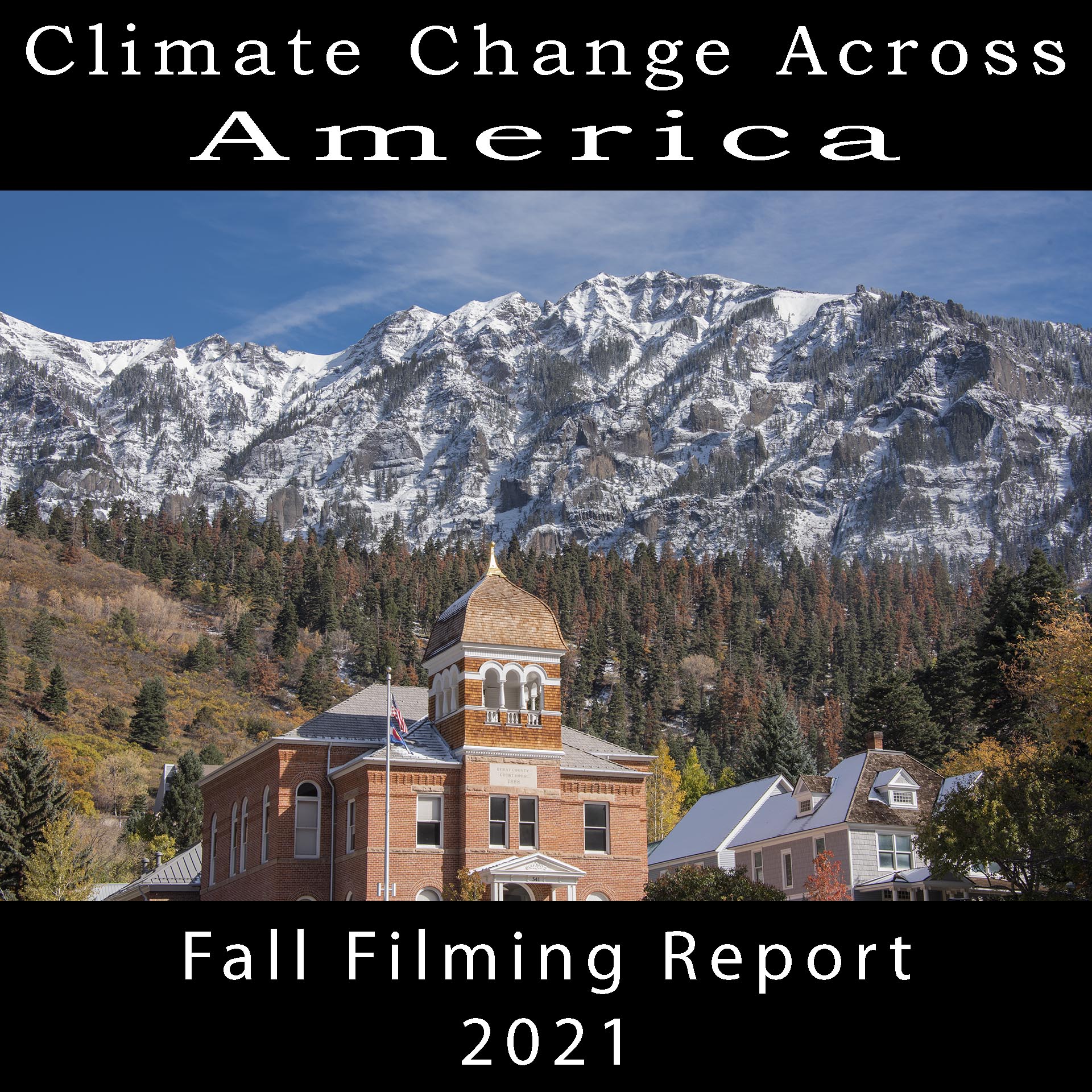

Climate Change Across America Fall Filming Report

Southern and Southwestern Colorado Beetle Attack and Forest Regeneration Failure at Mesa Verde National Park

We returned to filming after a long covid. No trouble. On the big drive from Texas to the mountains, New Mexico was grand with their indoor mask mandate. Colorado and Texas were about the same. Too darn many folks running about unmasked to take this pandemic seriously and limit even more mutations.

The cover image is Ouray’s County Courthouse with their ongoing fir beetle attack. This attack is from a native bark beetle, is about four or five years old and the fir beetle attack mortality creates the brightest imaginable red killed trees.

We spent our two weeks in southern and southwestern Colorado as usual looking for climate change. Our mission this trip was to shoot — all in one frame — golden aspen, red conifers, blue sky, pink granite and white snow, but that wasn’t to happen this trip. We spent our time wandering and marvelling at the beauty of our world, climate change and all, camping except for a few nights after the first cold snow of the season.

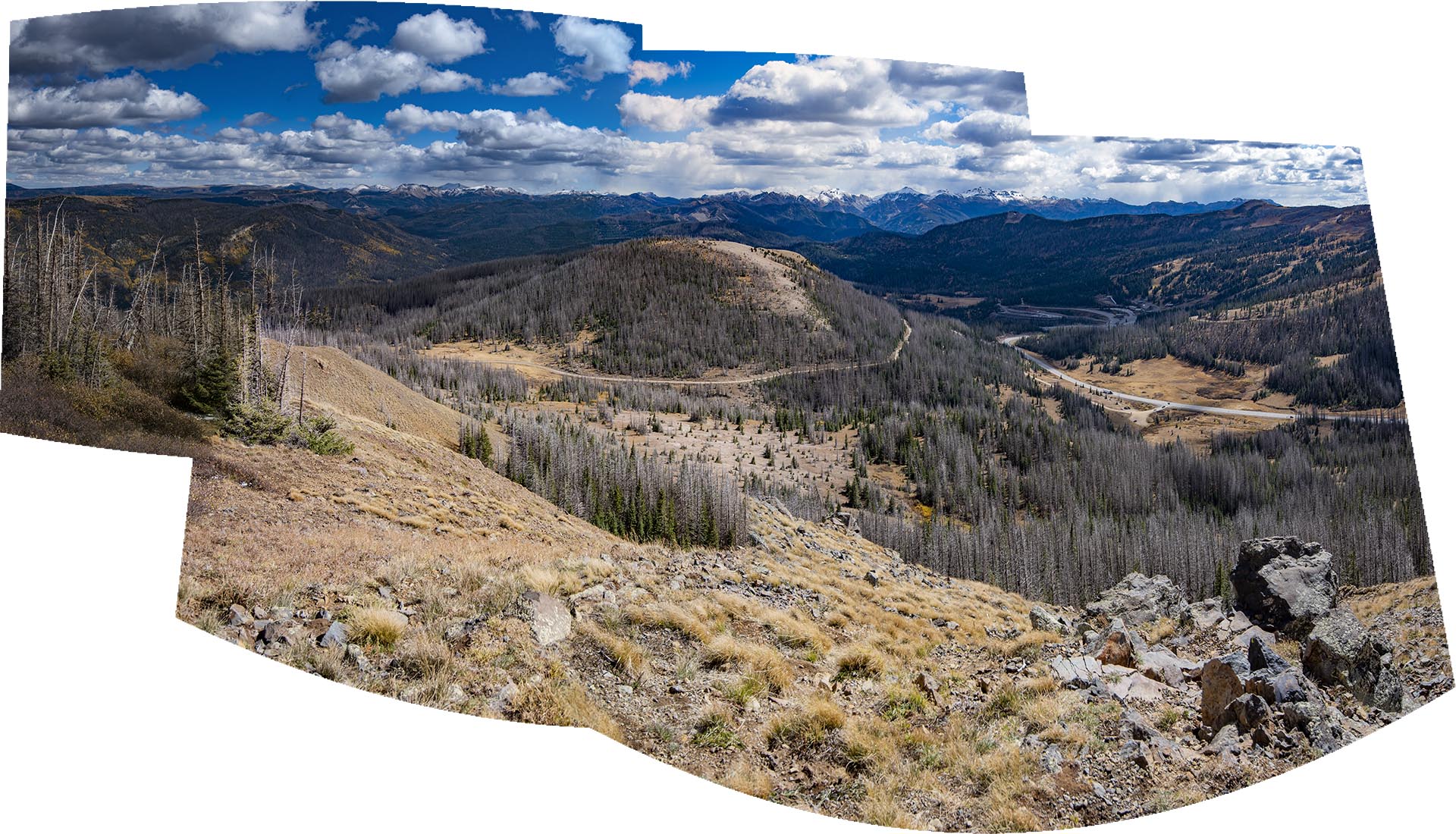

The beetle kill of course continued to be exceedingly widespread above 9,000 or 10,000 feet in elevation. The higher elevation forest in southwest Colorado is mostly spruce, so the spruce bark beetles are the culprits. This attack began in the early 2000s in the Weminuche Wilderness between Durango, Silverton and Creede, and quickly spread to a million acres. It is now as far east as central Colorado and south down to northern New Mexico. All together it is likely the kill is now at least 3 million acres. Above 10,000 feet in many areas it is almost complete. Below 10,000 it is sporadic and slowly to moderately increasing.

This panorama from the overlook atop Wolf Creek Pass at 11,660 feet elevation tells the story of climate change-caused bark beetle mortality. Very few spruce have escaped. A lot of the green around the edges are lodgepole pines or alpine fir. There are numerous species of native bark beetle that specialize in only certain species of trees.

This image is Mount Cinco Baldy, elevation 13,383, in the La Garita Mountains of south central Colorado between Creede and Lake City, in the La Garita Wilderness. The photo was taken at about 11,000 feet on Colorado 149. Treeline here is about 12,500 feet. You can see some green forest on the right and scattered in the lower areas. A little of the brown is aspen, your can tell the difference between aspen and spruce or other conifers because the aspen have a fuzzy appearance and the conifers have pointed tops.

This image is Mount Cinco Baldy, elevation 13,383, in the La Garita Mountains of south central Colorado between Creede and Lake City, in the La Garita Wilderness. The photo was taken at about 11,000 feet on Colorado 149. Treeline here is about 12,500 feet. You can see some green forest on the right and scattered in the lower areas. A little of the brown is aspen, your can tell the difference between aspen and spruce or other conifers because the aspen have a fuzzy appearance and the conifers have pointed tops.

Our first morning out. DJ makes warm bagels to go with coffee and tea at La Junta Campground near Tres Ritos, east of Taos on New Mexico 518. It was frosty! Why didn’t we think to paint our picnic tables when we were younger?

Our first morning out. DJ makes warm bagels to go with coffee and tea at La Junta Campground near Tres Ritos, east of Taos on New Mexico 518. It was frosty! Why didn’t we think to paint our picnic tables when we were younger?

La Junta Canyon, northeast New Mexico. This is what the beginnings of a beetle attack look like. There are some gray bones of lodgepole pine here and there that are hard to see, but what is called “spotting” is visible in the as the red kill, or lodgepole pines that have turned red because of bark beetle-caused mortality. It’s just a few trees at first that pop up every year with new “spots” forming more and more, especially in drier years, until the red coalesces across the entire mountain. The needles redden the first year after a successful attack kills a tree, then fall off after one to four years depending on the altitude. Red needles stay on longer at higher altitudes because so much of the time everything is preserved because the temperature is below freezing.

La Junta Canyon, northeast New Mexico. This is what the beginnings of a beetle attack look like. There are some gray bones of lodgepole pine here and there that are hard to see, but what is called “spotting” is visible in the as the red kill, or lodgepole pines that have turned red because of bark beetle-caused mortality. It’s just a few trees at first that pop up every year with new “spots” forming more and more, especially in drier years, until the red coalesces across the entire mountain. The needles redden the first year after a successful attack kills a tree, then fall off after one to four years depending on the altitude. Red needles stay on longer at higher altitudes because so much of the time everything is preserved because the temperature is below freezing.

What a celebration of yellow is this glorious image of quaking aspens at Cathedral Campground on Embargo Creek near Del Norte and South Fork. Aspen’s are having trouble too, but right now their trouble is mainly during drought pulses, which are unfortunately merging into one continuous drought. It’s the warming that is creating everlasting drought conditions, not necessarily lack of precipitation, but too little precip badly compounds drought response. The reason drought is becoming continuous even with normal precipitation is something called the nonlinear thermodynamic response. This is where a little bit of warming does not create a little bit more evaporation. Like so many things in climate change, it creates a lot more evaporation. The loss of precious water from water bodies, soils, and plants all increase nonlinearly with warming creating nonlinearly more stress in plants and leading to so much evaporation that to the plants, the dryness appears as if it were identical to drought with reduced precipitation. Stress from drought in trees and other long-lived species lasts for decades and longer in longer lived species making them more susceptible to insects, disease, and mortality from lack of water.

What a celebration of yellow is this glorious image of quaking aspens at Cathedral Campground on Embargo Creek near Del Norte and South Fork. Aspen’s are having trouble too, but right now their trouble is mainly during drought pulses, which are unfortunately merging into one continuous drought. It’s the warming that is creating everlasting drought conditions, not necessarily lack of precipitation, but too little precip badly compounds drought response. The reason drought is becoming continuous even with normal precipitation is something called the nonlinear thermodynamic response. This is where a little bit of warming does not create a little bit more evaporation. Like so many things in climate change, it creates a lot more evaporation. The loss of precious water from water bodies, soils, and plants all increase nonlinearly with warming creating nonlinearly more stress in plants and leading to so much evaporation that to the plants, the dryness appears as if it were identical to drought with reduced precipitation. Stress from drought in trees and other long-lived species lasts for decades and longer in longer lived species making them more susceptible to insects, disease, and mortality from lack of water.

Cathedral Rock at Cathedral Campground. You can see some gray spruce bones to the lower right of the rock.

Cathedral Rock at Cathedral Campground. You can see some gray spruce bones to the lower right of the rock.

More of the Cathedral Group with gray bones moderately scattered and red kill in two spots. The leafless sticks in the foreground are apsen that have lost their leaves. A few are dead, killed by aspen decline that gets worse during drought peaks. The dead aspen have fewer small limbs as they have fallen since the trees succumbed. One can tell leafless aspen from dead conifers at a distance because the aspen tops have a fuzzy appearance and the conifers have pointed tops.

More of the Cathedral Group with gray bones moderately scattered and red kill in two spots. The leafless sticks in the foreground are apsen that have lost their leaves. A few are dead, killed by aspen decline that gets worse during drought peaks. The dead aspen have fewer small limbs as they have fallen since the trees succumbed. One can tell leafless aspen from dead conifers at a distance because the aspen tops have a fuzzy appearance and the conifers have pointed tops.

A wonderfully cold and wet breakfast at Cathedral Campground, camp 2, with the temperature around 40. What a relief after the texas blowtorch season. It was 90 in Austin a few days before we departed.

A wonderfully cold and wet breakfast at Cathedral Campground, camp 2, with the temperature around 40. What a relief after the texas blowtorch season. It was 90 in Austin a few days before we departed.

This is lodgepole pine spotting at Cathedral. Such astonishing and beautiful color these beetles create., and no, at no other time do living conifers needles turn red, at least any of them in this report. I like to remind everyone that these Earth systems collapses we are experiencing are natural. The cause of course us and our climate pollution. Literally more than 100 percent of the cause is us because much of our climate pollution is global cooling aerosols that have masked about 0.5 C of warming. If it weren’t for the global cooling aerosols, our temperature would be 1.5 C warmer than normal right now, not the 1.0 degrees warmer than normal that it was last year. These natural Earth systems collapses are more rare than anything humankind has ever experienced. The opportunity for learning likewise, is unparalleled. We can stop these so called “irreversible” collapses, but we must lower our warming limit to below the tipping threshold where these collapses started as once started, even with no additional warming, the collapses complete. This range of safe temperature or the maximum warming limit is our current temperature, or whatever temperature cooler than today’s 1.0 degrees C warming above normal from 200 years ago when these collapses began. The collapses are also directly related to climate tipping, or what happens to our Earth systems when their evolutionary boundaries are exceeded. With the beetles, because the collapses began about the turn of the century, the safe temperature is less than 0.5 degrees C warming, at least for most high altitude and high latitude ecologies. These collapses also extend to lower altitude species like the pinyon pine in the Four Corners region that we detail later in this report.

This is lodgepole pine spotting at Cathedral. Such astonishing and beautiful color these beetles create., and no, at no other time do living conifers needles turn red, at least any of them in this report. I like to remind everyone that these Earth systems collapses we are experiencing are natural. The cause of course us and our climate pollution. Literally more than 100 percent of the cause is us because much of our climate pollution is global cooling aerosols that have masked about 0.5 C of warming. If it weren’t for the global cooling aerosols, our temperature would be 1.5 C warmer than normal right now, not the 1.0 degrees warmer than normal that it was last year. These natural Earth systems collapses are more rare than anything humankind has ever experienced. The opportunity for learning likewise, is unparalleled. We can stop these so called “irreversible” collapses, but we must lower our warming limit to below the tipping threshold where these collapses started as once started, even with no additional warming, the collapses complete. This range of safe temperature or the maximum warming limit is our current temperature, or whatever temperature cooler than today’s 1.0 degrees C warming above normal from 200 years ago when these collapses began. The collapses are also directly related to climate tipping, or what happens to our Earth systems when their evolutionary boundaries are exceeded. With the beetles, because the collapses began about the turn of the century, the safe temperature is less than 0.5 degrees C warming, at least for most high altitude and high latitude ecologies. These collapses also extend to lower altitude species like the pinyon pine in the Four Corners region that we detail later in this report.

The mighty Rio Grande River near Wagon Wheel Gap where the river is crowded between cliffs. This is one of only a few shots where we came close to capturing redkill and yellow aspen in the same shot. There is a fair amount of red on the ridge, and a tiny spot of yellow.

The mighty Rio Grande River near Wagon Wheel Gap where the river is crowded between cliffs. This is one of only a few shots where we came close to capturing redkill and yellow aspen in the same shot. There is a fair amount of red on the ridge, and a tiny spot of yellow.

Also near Wagon Wheel Gap, it’s easy to see the progression from red to brown to gray of the beetle killed trees with the red and brown in front from new attack, and the large number of gray sticks on the ridge above.

Also near Wagon Wheel Gap, it’s easy to see the progression from red to brown to gray of the beetle killed trees with the red and brown in front from new attack, and the large number of gray sticks on the ridge above.

Another shot of the mighty Rio Grande near Wagon Wheel Gap with gray bones on the ridge in the background. The stately tree leaning out over the river on the right with the orange bark, fluffy needles masses and stately limbs is a ponderosa pine. The pointy blue ones are blue spruce. The gray on the ridge is either lodgepole pine or Engelmann spruce.

Another shot of the mighty Rio Grande near Wagon Wheel Gap with gray bones on the ridge in the background. The stately tree leaning out over the river on the right with the orange bark, fluffy needles masses and stately limbs is a ponderosa pine. The pointy blue ones are blue spruce. The gray on the ridge is either lodgepole pine or Engelmann spruce.

This striking telephoto panorama of spruce bones is from the overlook at Wolf Creek Pass.

This striking telephoto panorama of spruce bones is from the overlook at Wolf Creek Pass.

Palisades Campground, north of Pagosa Springs on the edge of the Weminuche Wilderness. The flanks of the high mountains are full of gray spruce bones.

Palisades Campground, north of Pagosa Springs on the edge of the Weminuche Wilderness. The flanks of the high mountains are full of gray spruce bones.

This is a crop of the above image from Palisades Campground showing the gray killed spruce on the mountain’s flanks.

This is a crop of the above image from Palisades Campground showing the gray killed spruce on the mountain’s flanks.

Frost prisms in the meadow next to camp at Palisades.

Frost prisms in the meadow next to camp at Palisades.

The violet crown at Palisades. This is a phone panorama btw.

The violet crown at Palisades. This is a phone panorama btw.

We ran into a long-lost friend at our mandatory Lake City ice cream stop.

We ran into a long-lost friend at our mandatory Lake City ice cream stop.

Big Meadows Reservoir Campground, 9,217 feet, spruce beetle kill and aspen, US 160 west of South Fork. This mountainside of spruce kill was a tough shot that I thought wouldn’t make. Thankyou Photoshop! The green around the edges are blue spruce. The yellow is aspen. The others that are mostly dead are the more widespread Engelmann spruce. Bark beetles are quite specific in which species of trees they attack and before climate change were never known to attack species other than their preferred. So the Engelmann spruce bark beetle has nothing to do with the blue spruces. The mountain pine beetle that has been responsible for over 70 million acres of kill across western North America, became so numerous at one point that it began eating spruce and fir instead of their favorites, lodgepole and ponderosa pine.

Big Meadows Reservoir Campground, 9,217 feet, spruce beetle kill and aspen, US 160 west of South Fork. This mountainside of spruce kill was a tough shot that I thought wouldn’t make. Thankyou Photoshop! The green around the edges are blue spruce. The yellow is aspen. The others that are mostly dead are the more widespread Engelmann spruce. Bark beetles are quite specific in which species of trees they attack and before climate change were never known to attack species other than their preferred. So the Engelmann spruce bark beetle has nothing to do with the blue spruces. The mountain pine beetle that has been responsible for over 70 million acres of kill across western North America, became so numerous at one point that it began eating spruce and fir instead of their favorites, lodgepole and ponderosa pine.

This is a telephoto of the above mountainside at Big Meadows Reservoir Campground. Mortality here is likely over 60 or 70 percent. You can also tell beetle kill from forest fire because there is no black, and all the little limbs remain on the trees. With fire, there’s black and all the little limbs are burned off.

This is a telephoto of the above mountainside at Big Meadows Reservoir Campground. Mortality here is likely over 60 or 70 percent. You can also tell beetle kill from forest fire because there is no black, and all the little limbs remain on the trees. With fire, there’s black and all the little limbs are burned off.

Snow! Mesa Verde! Cold!

Snow! Mesa Verde! Cold!

We went to ‘Rango for a few days and stayed at the Caboose Motel, then wandered north up towards Silverton and Ouray in the big snow. At least, it was big snow for us Texians with five to ten inches on the passes on the way north.

We went to ‘Rango for a few days and stayed at the Caboose Motel, then wandered north up towards Silverton and Ouray in the big snow. At least, it was big snow for us Texians with five to ten inches on the passes on the way north.

Near Purgatory Ski Resort on Colorado 160 north of Durango, elevation 8,800 feet. Mostly the forest is in decent shape this low, but there are three spruces with their bones bared center screen. Small groupings like this are typical.

Near Purgatory Ski Resort on Colorado 160 north of Durango, elevation 8,800 feet. Mostly the forest is in decent shape this low, but there are three spruces with their bones bared center screen. Small groupings like this are typical.

First snow of the season, South Mineral Creek Canyon near South Mineral Campground and the Ice Lakes Trailhead for those of you who have been on one of the Club’s Colorado trips to the San Juan Mountains.

First snow of the season, South Mineral Creek Canyon near South Mineral Campground and the Ice Lakes Trailhead for those of you who have been on one of the Club’s Colorado trips to the San Juan Mountains.

South Mineral Creek Canyon near Silverton. No beetle kill here, just pretty. This canyon is deep in the heart of the mountains in southwest Colorado and is slowly seeing an increase in mortality but as yet has not seen an epic attack.

Durango Silverton Rio Grande Railroad Engine 480 leaves Silverton for Durango with a load of chilly tourists. The bare trunks in the background are healthy aspen.

Durango Silverton Rio Grande Railroad Engine 480 leaves Silverton for Durango with a load of chilly tourists. The bare trunks in the background are healthy aspen.

The beetles here on the Million Dollar Highway are not bad; Colorado 160, between Silverton and Ouray looking back towards Silverton to the south. Get em while you can, if you can drive the Million Dollar Highway! It’s paved, but one of those noted highways with no guard rails… or shoulders. Just straight down.

The beetles here on the Million Dollar Highway are not bad; Colorado 160, between Silverton and Ouray looking back towards Silverton to the south. Get em while you can, if you can drive the Million Dollar Highway! It’s paved, but one of those noted highways with no guard rails… or shoulders. Just straight down.

La Plata River Canyon, west of Durango, 4×4 trail to the old mining settlement of La Plata City.

La Plata River Canyon, west of Durango, 4×4 trail to the old mining settlement of La Plata City.

Mesa Verde National Park, Long Mesa Fire 2002. Around the turn of the century a strong drought pulse struck the four-corners region. Five named fires burned more than 50 percent of the park. The forest on top of the mesas likely received even more damage as fires don’t burn well in canyons. In combination with direct drought kill and pinyon beetle kill, forest mortality is even higher. None of the forest is regenerating and this is highly unusual, in our old climate. Across the American West, a third of forest burned around the turn of the century and since, are not regenerating at all, it’s just too dry. Of the remainder, about half are only regenerating at half the rate of the 20th century. At Mesa Verde, their former pinyon/juniper forests were right on the edge of the desert making them more prone to these kind of climate change impacts. Literally before our eyes, these forests have changed into grasslands.

Mesa Verde National Park, Long Mesa Fire 2002. Around the turn of the century a strong drought pulse struck the four-corners region. Five named fires burned more than 50 percent of the park. The forest on top of the mesas likely received even more damage as fires don’t burn well in canyons. In combination with direct drought kill and pinyon beetle kill, forest mortality is even higher. None of the forest is regenerating and this is highly unusual, in our old climate. Across the American West, a third of forest burned around the turn of the century and since, are not regenerating at all, it’s just too dry. Of the remainder, about half are only regenerating at half the rate of the 20th century. At Mesa Verde, their former pinyon/juniper forests were right on the edge of the desert making them more prone to these kind of climate change impacts. Literally before our eyes, these forests have changed into grasslands.

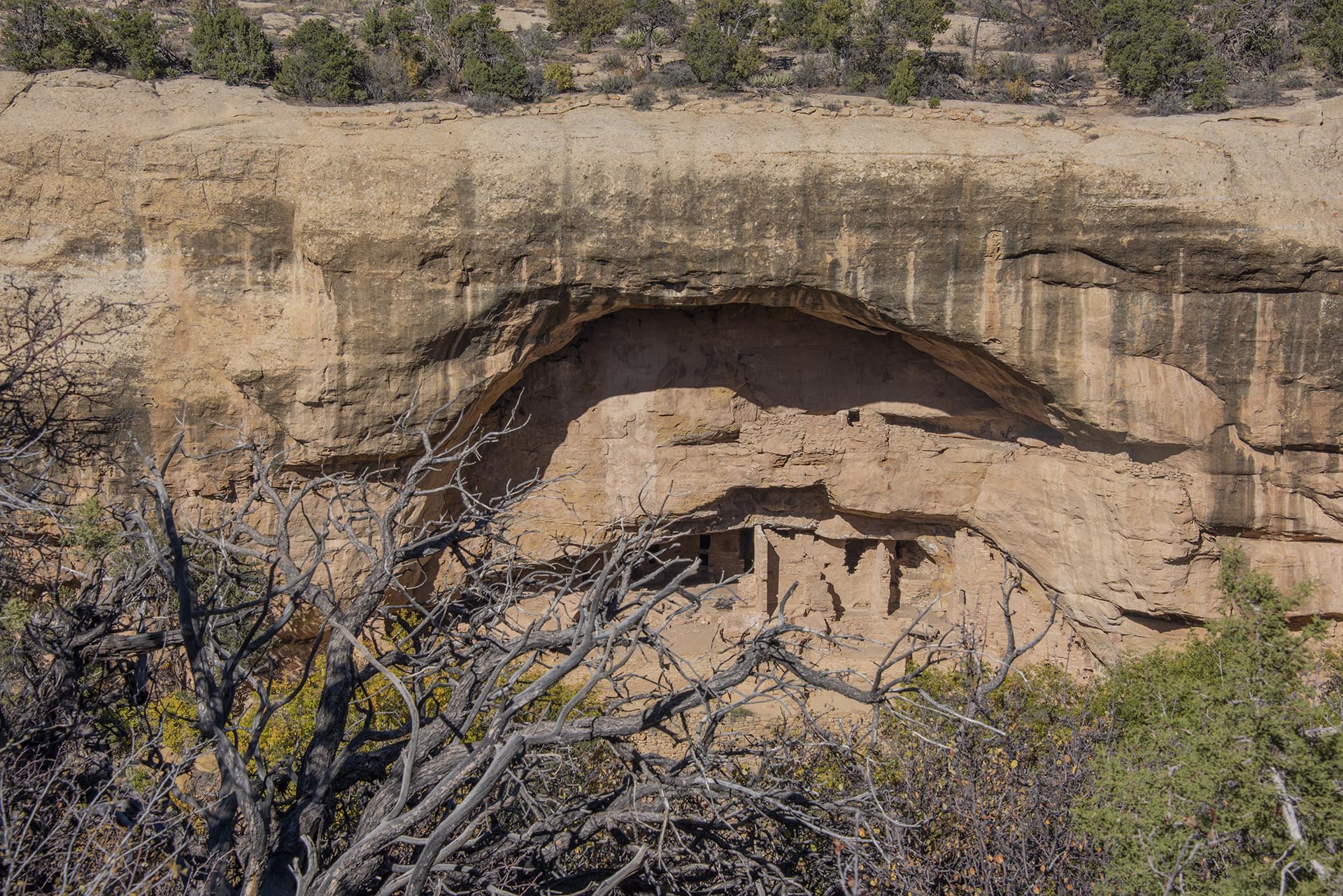

Square Tower House. Epic drought 700 years ago drove the Anazazi away from their paradise. Today’s climate change at Mesa Verde is likely worse. One doesn’t normally see people in these ancient ruins except for ranger guided tours. These were forest service or research personnel.

Square Tower House. Epic drought 700 years ago drove the Anazazi away from their paradise. Today’s climate change at Mesa Verde is likely worse. One doesn’t normally see people in these ancient ruins except for ranger guided tours. These were forest service or research personnel.

Long Mesa Fire 2002 Panorama. Zero forest regeneration. Beautiful grassland.

Long Mesa Fire 2002 Panorama. Zero forest regeneration. Beautiful grassland.

Long Mesa Fire 2002, La Plata Mountains in background.

Long Mesa Fire 2002, La Plata Mountains in background.

This image was taken from the old campground near Spruce Tree House. The yellow is mostly scrub oak that is regenerating as it is a more drought and heat tolerant species than the pinyon and juniper that are not regenerating.

This image was taken from the old campground near Spruce Tree House. The yellow is mostly scrub oak that is regenerating as it is a more drought and heat tolerant species than the pinyon and juniper that are not regenerating.

The wild mustangs like the new rangeland.

The wild mustangs like the new rangeland.

Trail to Square Tree House. This is a typical scene of the forests that remain in Mesa Verde. Mortality here is from drought or beetles at the turn of the century. Ancient pinyon pine in Mesa Verde can be over 1,000 years old.

Trail to Square Tree House. This is a typical scene of the forests that remain in Mesa Verde. Mortality here is from drought or beetles at the turn of the century. Ancient pinyon pine in Mesa Verde can be over 1,000 years old.

This is typical recent pinyon pine beetle kill. There are still some red needles on this one.

This is typical recent pinyon pine beetle kill. There are still some red needles on this one.

Pitch tubes on a recently killed pinyon pine. When the bark beetles bore through the bark of a tree to lay their eggs, the tree tries to “pitch” the beetles out with sap and produces these small sap nodules on the trunk of the tree. Red killed needles are still on this one too.

Pitch tubes on a recently killed pinyon pine. When the bark beetles bore through the bark of a tree to lay their eggs, the tree tries to “pitch” the beetles out with sap and produces these small sap nodules on the trunk of the tree. Red killed needles are still on this one too.

I had a ranger tell me it takes up to 200 years years for these forests to regenerate after fire and one trailside exhibit said 100 years. The sad reality is that this statement is true for a forest to mature after fire. In these dry desert climates, pinyon and juniper grow very slowly. Regeneration however, this statement is about maturity of a forest, not regeneration of the forest. If trees do not start to regrow or regenerate, they will never mature and this is what is happening here and across the West. These forests should be pocket to chin high in regenerating trees. This photo is of a small unburned area with a regenerating pinyon. The ancient bones are juniper and pinyon, killed by either fire, beetles or drought. You can usually tell the juniper because they are multi branched from near the base and pinyon’s are more single-stemmed. Edges of burned areas are the only places where regeneration is taking place because the fires did not burn as extremely along their edges, and nursery conditions now remain that help regenerating trees. The live roots of a growing forest, plus the organic detritus that mulches the ground, server to retain water and create these nursery conditions.

I had a ranger tell me it takes up to 200 years years for these forests to regenerate after fire and one trailside exhibit said 100 years. The sad reality is that this statement is true for a forest to mature after fire. In these dry desert climates, pinyon and juniper grow very slowly. Regeneration however, this statement is about maturity of a forest, not regeneration of the forest. If trees do not start to regrow or regenerate, they will never mature and this is what is happening here and across the West. These forests should be pocket to chin high in regenerating trees. This photo is of a small unburned area with a regenerating pinyon. The ancient bones are juniper and pinyon, killed by either fire, beetles or drought. You can usually tell the juniper because they are multi branched from near the base and pinyon’s are more single-stemmed. Edges of burned areas are the only places where regeneration is taking place because the fires did not burn as extremely along their edges, and nursery conditions now remain that help regenerating trees. The live roots of a growing forest, plus the organic detritus that mulches the ground, server to retain water and create these nursery conditions.

A crop of the above regenerating pinyon pine.

A crop of the above regenerating pinyon pine.

These two regrowing junipers in the lower right of the image, are only in this spot because of the roadside ditch supplying more water. Please note; the other small green regrowing-like plants are various species of shrubs or scrub oak that can tolerate drought better than pinyon and juniper.

These two regrowing junipers in the lower right of the image, are only in this spot because of the roadside ditch supplying more water. Please note; the other small green regrowing-like plants are various species of shrubs or scrub oak that can tolerate drought better than pinyon and juniper.

Cliff Palace and red kill pinyon pine on top of the mesa.

Cliff Palace and red kill pinyon pine on top of the mesa.

New Fire House and recent pinyon pine killed by bark beetles.

New Fire House and recent pinyon pine killed by bark beetles.

New Fire House crop from image above.

New Fire House crop from image above.

Oak Tree House and Pinyon bones.

Oak Tree House and Pinyon bones.

Cliff dwellings and beetle killed pinyons are everywhere.

Cliff dwellings and beetle killed pinyons are everywhere.

There are over 600 ruins at Mesa Verde. This photo is a post processed experimental double exposure, near and far focus. The near focus was to highlight the dead branches from a beetle killed pinyon.

There are over 600 ruins at Mesa Verde. This photo is a post processed experimental double exposure, near and far focus. The near focus was to highlight the dead branches from a beetle killed pinyon.

Long Mesa Fire 2000.

Long Mesa Fire 2000.

A crop from the above panorama shows a small amount of forest remaining across the top of the mesa in the far ground, with the La Plata Mountains in the background.

A crop from the above panorama shows a small amount of forest remaining across the top of the mesa in the far ground, with the La Plata Mountains in the background.

Climate change is a dirty job.

Climate change is a dirty job.