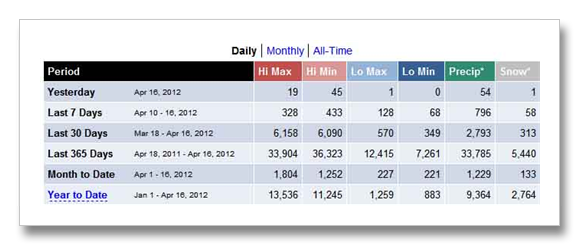

In the twelve months prior to April 16, high temperature records outnumbered low temperature records 3 to 1.

James Hansen told the U.S. Senate in 1988 that “it is time to stop waffling so much and say that the evidence is pretty strong that the greenhouse effect is here.” After all of the recent unprecedented weather extremes globally, many of which were extremely cataclysmic and didn’t hardly make the U.S. news, we get this paper from the prestigious Nature Climate Change (where the authors of the paper state): “We conclude that now, more than 20 years later (after the Hansen Senate testimony), the evidence is strong that anthropogenic, unprecedented heat and rainfall extremes are here — and are causing intense human suffering.”

NOAA reports that the in the last 365 days, 240 record all-time high temperature records were set in the U.S. vs. 6 (six) all-time record low temperature records. In a normal climate, the number of high temperature records should be about equal to the number of low temperature records.

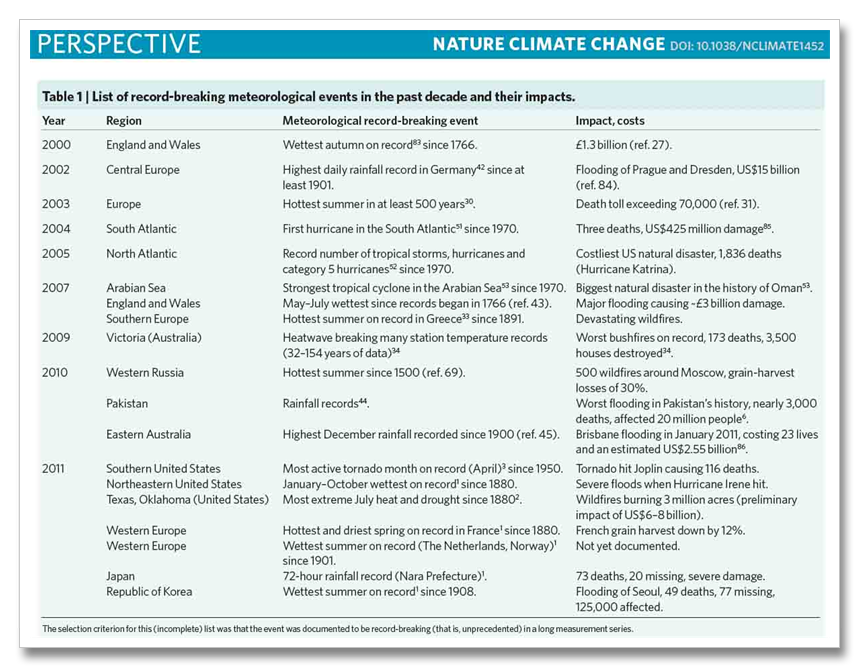

A record 753 tornadoes spun from the sky in April 2011 which smoked the previous record of 542 set in just May 2003. The authors tell us; “Other regions in the world were affected by extreme weather in 2011 as well: rainfall records were set in Australia, Japan and Korea, whereas the Yangtze Basin in China experienced record drought. In western Europe, spring was exceptionally hot and dry, setting records in several countries.” The last decade though, really tells the story in physical damage and human suffering. A partial and incomplete list from the paper is presented below:

The authors tell us that the reason they chose to highlight the above disasters is because they are all “exceptional and unprecedented.” These kind of things have not happened before during modern record keeping. The authors go on: “The [2010] Moscow heat wave and Pakistan flooding that year illustrated how destructive extreme weather can be to societies: the death toll in Moscow has been estimated at 11,000 and drought caused grain-harvest losses of 30%, leading the Russian government to ban wheat exports. At the same time Pakistan was hit by the worst flooding in its history, which affected approximately one-fifth of its total land area and 20 million people.” The World Meteorological Organization issued a statement on the “unprecedented sequence of extreme weather events”, in August 2010. They stated that these unprecedented extreme weather events “match Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projections of more frequent and more intense extreme weather events due to global warming”.

Now comes the discussion of the links to climate change and while sobering they are fascinating as well. The decade of 1990 to 2000 was the hottest decade ever recorded, until the 20th century came along. Now the decade 2000 to 2010 is the hottest decade ever. The simple physical science behind how extreme weather becomes more extreme with rising temperature alone is enough to friz your hair. High temperature records have doubled while low temperature records have been halved. In a stable climate world, there would be an equal number of high and low temperature records. Air rises faster the hotter it is, the faster rising air creates more violent storms.

Warming leads to more evaporation. Each degree F warmer allows the atmosphere to hold 4 percent more moisture. This moisture comes from water bodies and oceans and it comes from plants and the soil. Four percent may not sound like much, but what if most of these extreme weather events were happening during months where the average temperature was five or six degrees warmer than normal (they generally are by the way). This makes formerly extreme storms even more extreme. It increases rainfall of course, but the warmer temperature increases winds as well. It increases updrafts which hold hail up in the cloud tops longer making the hailstones bigger. The increased winds make tornadoes more likely to form and it makes them more violent. The increased updrafts increase friction which increases static electrical discharge–lightning. Same thing happens in winter. Remember that old saying “too cold to snow”? The saying is true, or relatively true. Like discussed above, each degree of warming or cooling changes the capacity of the air to hold moisture by four percent. So the colder the air is the less moisture it can hold. This means that the nearer freezing it is (warmer), the more snow comes from any given storm–CaPOW! Snowmeggedon!

The opposite is true as well. The extra drying from the extra heat, when precipitation triggers are absent, acts as a feedback mechanism. The hotter it gets, the drier it gets and the drier conditions allow it to get even hotter, which completes the feedback loop until, like in Austin, Texas in 2010, we had 90 days of 100 degree plus heat when our average is only 12. We had less rainfall in a 12-moth period in 2011 than we had experienced since record keeping began in the 1850s.

So it’s not just billions of dollars, it is statistics that are telling us that our climate has changed. The statistics of extreme weather are much more simple than other weather statistics. One of the most common questions asked of climate scientists is that age old question “was this or that weather event caused by climate change?” The answer is one that almost always leaves the public with a misunderstanding. There is no yes or no answer to this question so when the scientists says it is difficult to tell, the public usually takes that as a “no,” when this is not the case at all. The correct answer involves probabilities, or chances of happening with a given amount of warming. But extreme events are different. Unprecedented weather events, or events like 100-years storms that happen only very rarely, can be very easy to say are caused by climate change with a high degree of certainty. This is exactly what we have been seeing in many places.

The scary part now is that the changes have just begun. We have decades of change stored up in the pipeline because our climate does not react immediately to changes in greenhouse gas concentration. The tremendous cooling capacity of our oceans and ice sheets sees to that. And now we have the Asian Brown Cloud to contend with. I’ve not reported on that lately, but it’s still there and still growing with a mask of about 1.2 degrees F of cooling already. What this means is that, if all of the sudden, China and India stopped emitting the smog forming pollutants that form the Asian Brown Cloud, Earth’s temperature would rapidly jump 1.2 degree F. This is almost as much warming as we have seen in the entire post industrialized world for the last 150 to 200 years.

Coumou and Rahmstorf, A decade of weather extremes, Nature Climate Change, March 26, 2012.

Press Release: http://www.pik-potsdam.de/news/press-releases/wetterrekorde-als-folge-des-klimawandels-ein-spiel-mit-gezinkten-wurfeln