First Published on Truthout, March 18, 2014

Today, we are burning fossil carbon one million times faster than it was naturally put in the ground, and carbon dioxide is increasing 14,000 times faster than anytime in the last 610,000 years (1,2). Climate is now changing faster than it has during any other time in 65 million years – 100 times faster than the Paleocene/Eocene extinction event 56 million years ago see here.(3) However, “climate change” is not the most critical issue facing society today; abrupt climate change is. Climate scientists now have the knowledge necessary to guide us beyond existing climate pollution policy. New policy needs to focus on abrupt climate change, not the relatively slow changes we see in climate models of our future. The social, economic and biological disruptive potential of abrupt climate change is far greater than that of the gradual climate change present policy is predicated upon.

Over about the last 100,000 years, the world has seen about 20 abrupt climate changes, averaging 9 to 14 degrees, including in Greenland, where the temperature changed up to 25 to 35 degrees. These abrupt climate changes happen 10 to 100 times faster than the climate change projections we have all come to know and love. Mostly they happened in several decades or less, but one of the biggest changes happened in just a few years. (4)

The evidence of these abrupt changes is clear in the highly accurate findings from ancient preserved air in ice sheets. They were likely all related to feedbacks and thresholds or tipping points. There are many different kinds of feedbacks and tipping points and the science is still unclear on many of them. Feedbacks are things like the snow and ice feedback loop: snow and ice reflect up to 90 percent of the sun’s energy back into space harmlessly as light, while ocean, rocks, soil, vegetation and etc. reflect only 10 percent back into space, and the rest is absorbed and turned into heat energy that gets trapped by the greenhouse effect. The trapped energy creates more warming, that melts more snow and ice, that absorbs even more energy, changing it into heat, and the loop continues until all the snow and ice are gone.

Tipping points are a little bit more difficult to describe in environmental systems, but can easily be described in other ways. A canoe has a tipping point, beyond which a dry lovely day on the water turns into something quite different. Environmental systems behave in a similar manner. We can dump a lot of water pollution into our lakes and rivers, and nothing major seems to happen. Degradation occurs, but the lake or river generally continues to behave like a lake or river until the pollution levels reach a critical point. Then, as when one leans over just a little too far in a canoe, an algae bloom happens and the lake or river turns green or brown overnight and gets really smelly and bad tasting. This is an ecosystem tipping point. Pollution levels (nutrients from wastewater treatment plants, urban stormwater runoff agriculture, etc.) accumulate over time to a sufficiently high level that finally, an algae population explosion occurs. Then a really devastating thing sometimes occurs if the tipping point is really critical. All the algae die, sink to the bottom and decompose simultaneously. The decomposition uses up all the oxygen in the water and there is a big fish kill on top of the stinky smelly unsightly algal bloom.

Our global environment is no different from a lake or river or even a canoe. Some of these 20 or so abrupt changes happened in direct response to tipping points that preceded them, like a shutdown of the North Atlantic portion of the Gulf Stream. Some of them happened because one or more feedbacks went out of control. Pinning down exact causes of the abrupt changes, however, remains a difficult task.

Unearthing the Evidence

Abrupt climate change wasn’t really a recognized phenomenon until about 20 years ago. Strong evidence of abrupt temperature changes had been found in the 1960s in Greenland ice cores, but they were poorly understood and considered anomalies at the time. Climate change science was dominated by sediment cores from oceans and lakes and slow, glacially paced changes of the 100,000-year cycles of our climate as Earth’s tilt and orbit changed around the sun. As time passed, the early evidence of abrupt change was found again and again in subsequent ice cores. Even in Antarctica, these same abrupt signals were found.

Bubbles of ancient air preserved in Greenland ice. (Photo: Bruce Melton)

Those first records of abrupt climate change from the 1960s at Camp Century were found in ice cores from a WWII nuclear base in the middle of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Camp Century was chosen as one of the first places to drill ice because it was an existing station in a very hostile environment. The Greenland Ice Sheet is over two miles thick and 11,000 feet high. The ice cores seemed to show radical climate jumps in the clearly visible annual layers of snow, in oxygen and methane in the preserved ancient air and dust that increased and decreased dramatically according to temperature.

Over the next two decades and continued ice core drilling, the same signs of abrupt changes were seen, and some confidence began to emerge about the validity of this amazing storehouse of evidence. It was not until the early 1990s, though, that the story became clear. Two identical ice cores were drilled in one of the most stable parts of the ice sheet. The cores were identical down to 100,000 years ago, then close to bedrock, the annual layers became warped and folded. Above the level of ice at 100,000 years ago, the ice cores matched identically. The same volcanic eruptions from across the world were represented by characteristic ash from the different eruptions. Even the same dust from Siberia during really cold dry periods was found in the different ice cores. These abrupt changes were real and they were radical. Why then did sediment cores not reveal abrupt changes?

Universally, these abrupt climate changes dwarf climate change projected by our world’s scientific institutions in their summaries of climate change projections

The reason was biopertubation. Bioperturbation is what happens to sediments when worms eat through organic material on the bottom of a lake or ocean. Dozens and even hundreds of years of sediment deposition per inch are mixed and remixed by the worms. It happens to almost all sediments everywhere. The best resolution in sediments at the time was really a century or more or even thousands of years. The abrupt nature of actual changes in the annual sediment layers was simply wiped out, or eaten up. Then we began to learn of areas of the globe where biopertubation did not exist.

A few areas of the ocean were identified that were stagnant and devoid of oxygen. Worms can’t live without oxygen and in these areas there is no bioperturbation. The same abrupt climate jumps as were found in Greenland were now plain to see. We have also found the same evidence in the annual layers of stalagmites and other cave formations.

It took another decade for science to catch up, but what we know now is that Earth’s climate normally changes through abrupt shifts. Climate change is mostly not a slow, glacially paced thing. The changes are fast and violent and leave ecosystems shredded in their wake. They start out slowly, but then a threshold is crossed, and the temperature jumps up or down far more radically than the slow and modest warming projected by almost all climate change models today. Universally, these abrupt climate changes dwarf climate change projected by our world’s scientific institutions in their summaries of climate change projections.

Extreme Impacts

With this new knowledge about abrupt climate change and the galactically large risks posed by abrupt climate change, the discussion about climate in our society today has become misplaced. Emission and eventual climate change are important, but they are fundamentally not in the same ballpark as abrupt change.

A new National Academy of Sciences mega-report takes on the prospect of future abrupt climate changes, asking whether changes may take place “so fast that the time between when a problem is recognized and when action is required shrinks to the point where orderly adaptation is not possible?”

The good news is that some of the more popular abrupt climate change scenarios are not likely, according to the report. Popularized and wildly exaggerated in movies like The Day After Tomorrow, a shutdown of ocean currents seems less likely in time frames that matter. Likewise, concern of serious trouble from methane outgassing from melting clathrates on the ocean floor and in permafrost seems unlikely. However, we do need to realize that the climate science consensus process is not flawless. That process told us in 2007 that Antarctica would not begin to lose ice until after 2100, but now tells us in the 2013 IPCC report that Antarctic ice loss has already caught up with Greenland’s. So, when climate change consensus opinion now tells us ocean current shutdown and clathrate off gassing are not very likely, we must understand that this opinion cannot be counted as fact.

Moreover, the mega-report notes that abrupt changes in ecosystems, weather and climate extremes and groundwater supplies critical for agriculture are not only more likely than previously understood, but also, impacts are more likely to be more extreme. (5) The report tells us that there are many more types of abrupt change than temperature and that science is now becoming good enough to help us anticipate some of them, but not all of them. It also tells us that some abrupt changes have already begun – like the crash of Arctic sea ice: “More open water conditions during summer would have potentially large and irreversible effects . . . because the Arctic region interacts with large-scale circulation systems of the oceans and atmosphere, changes in the extent of sea ice could cause shifts in climate and weather around the Northern Hemisphere.”

Current policy simply does not take abrupt climate change into consideration. The consensus reports all mention it sooner or later, but then they caveat their way out of doing anything about it because too little is known about how these things actually happen.

We have already seen how increasing energy in the Arctic has increased the magnitude of jet stream loops and the speed of those loops across the planet. These loops carry more intense storms (the polar vortex) and because of their retarded movement across the globe, these more intense weather systems stall out, increasing the dry, wet or otherwise extreme conditions associated with them.

New discoveries have shown that it is likely that one of the most abrupt of all climate changes in the last 100,000 years happened 12,000 years ago. It was called the Younger Dryas, and the temperature in Greenland jumped 25 degrees in three years. Some 1,000 years later, it fell 25 degrees in a few decades. This abrupt tipping point is now a prime candidate in the extinction of 72 percent of North American mammals, including large mammals like the saber-toothed cat and mastodon.

There are other types of abrupt changes that can be triggered by slow climate change. They are called abrupt climate impacts. The report gives the example of the mountain pika, one of my favorite alpine animals. (7) The pika is a bunny-sized, rabbit-like mammal with short little mouse-like ears and a peculiar little squeaky nasally call. It gathers grass and wildflowers in its home in the high mountains, mostly above treeline during the short high altitude summer, and stores this “pika hay” in caches in the rocks of scree slopes high on mountainsides.

As temperatures rise, the alpine meadows that the pika evolved with rise up the mountainside in response to warming. The alpine vegetation follows the cool zone up the mountain. At some point this process ends abruptly as the top of the mountain is reached and no place remains for the pika’s hay to grow. The Center for Biological Diversity has petitioned California and the US Fish and Wildlife Service to list the pika as endangered because of climate change, but has been turned down by both. Their reasoning is that the pika’s range is not in danger of disappearing in the next several decades. That is exactly what this article is about. Current policy simply does not take abrupt climate change into consideration. The consensus reports all mention it sooner or later, but then they caveat their way out of doing anything about it because too little is known about how these things actually happen. From the summary of “Abrupt Climate Change – Anticipating Surprises”:

Although many projections of future climatic conditions have predicted steadily changing conditions giving the impression that communities have time to gradually adapt, for example, by adopting new agricultural practices to maintain productivity in hotter and drier conditions, or by organizing the relocation of coastal communities as sea level rises, the scientific community has been paying increasing attention to the possibility that at least some changes will be abrupt, perhaps crossing a threshold or ‘tipping point’ to change so quickly that there will be little time to react. This concern is reasonable because such abrupt changes – which can occur over periods as short as decades, or even years – have been a natural part of the climate system throughout Earth’s history.

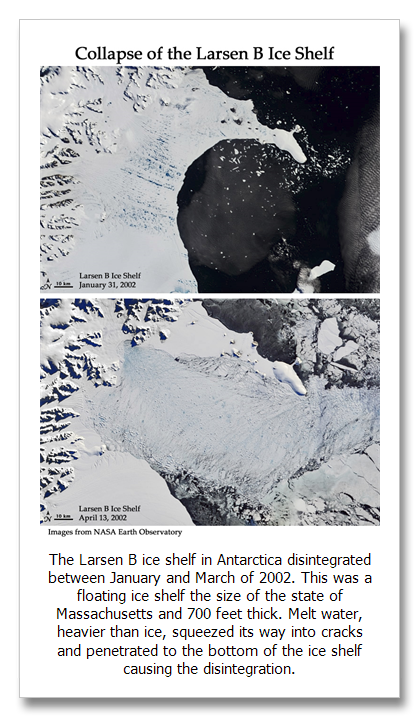

The Larsen B ice shelf in Antarctica disintegrated between January and March of 2002. This was a floating ice shelf the size of the state of Massachusetts and 700 feet thick. Melt water, heavier than ice, squeezed its way into cracks and penetrated to the bottom of the ice shelf causing the disintegration.

A much quicker example is the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The last time it happened 120,000 years ago, Earth was about the same temperature as it is today. We saw a similar collapse in 2003 when the Larsen B ice shelf, the size of Massachusetts, disintegrated in two months. Slow warming had created more and more melt on top of the Larsen B. Then a peculiar thing happened. The melt pools on top of the ice sheet became large enough and heavy enough (water is heavier than ice) to force cracks in the ice open. The cracks catastrophically opened all the way to the bottom of the floating ice sheet a thousand or more feet below and the entire thing broke into little bergy bits. We don’t know when this will happen to the Mexico-sized West Antarctic Ice Sheet (the largest remaining marine ice sheet), but we didn’t know a year ahead of time that collapse was going to happen to the Larsen B either. (8)

The current assumption as to how fast the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could collapse is a hundred years minimum. But the similarities in the Larsen B and the West Antarctic are high, and the consensus has wildly underestimated ice processes in Antarctica before.

Other possible abrupt climate impacts include ocean extinction events where hot spikes of weather chaos create widespread conditions beyond the evolution of ocean creatures. It’s the extremes that kill. We’ve seen previews in coral bleaching events across the world already. Seventy-five percent of complex coral reefs in the Caribbean have already been decimated. (9) Polar bears are at risk because their main prey, the ringed seal, rears its young on sea ice. The young ringed seals cannot swim until they mature – creating a large challenge for the perpetuation of that species with the absence of sea ice during the reproduction season. (10)

Drought alone killed “several” billion trees in the Amazon and now the Amazon is a net source of CO2, not a sink

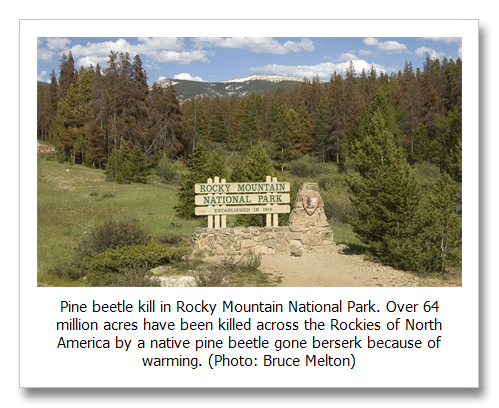

Another worrisome abrupt climate impact that is currently taking place has happened to 64 million acres of forest in the Rockies and billions of trees in the Amazon. In the Rockies, prolonged drought has been caused by warmer temperatures. Across the American West, the average temperature has been 70 percent greater than the global average and the increase is even greater at elevations where the forests are. This is a long-term shift in relative wetness, shown in the climate models and now being realized. (11) The growing season has increased by 30 days or more in the spring, which is relatively easy to measure because of the onset of snowmelt. (12) In the fall, it is more difficult to measure, but the longer growing season and the hotter temperatures both add to the warming feedback that has perpetuated drought even as normal rainfall has returned to some areas. The resulting stress from drought, along with the absence of extreme beetle-killing cold, has allowed a natural pine bark beetle to kill 20 times more trees than any attack ever recorded. (13)

Drought alone killed “several” billion trees in the Amazon and now the Amazon is a net source of CO2, not a sink. (14) In Texas, the drought has been perpetuated for nearly a decade with greater than average rainfall – more rain and the drought still continues because of increased evaporation. It killed over 300 million mature trees in the 2011 heat wave. (15)

Making Climate Science Real

So, what can we do to prepare for possible abrupt changes in the near future? The mega-report suggests setting up an Abrupt Change Early Warning System (ACEWS). Environmental systems often send out signals that a change of state is near. When weather flickers from cold to hot or wet to dry, it may be a sign that abrupt changes are to come. The ACEWS system would be integrated with a risk management system that takes into consideration the ultimate costs of an abrupt change. Example: coral bleaching events are certainly costly to some ocean systems and economies dependent on those ocean systems. An abrupt sea level jump, however, may not have near the impact on ocean systems, but have much more devastating impacts on global socio-economic factors.

Why are we not yet implementing these changes? A large part of the answer is that the perceived debate has masked the facts. Climate science is not real to most people.

Barring the creation of a full-blown abrupt change early warning system, scientists will continue to monitor ongoing changes and increase the accuracy of their measurements and their modeling efforts to simulate and recreate future and past change events. But as more knowledge on abrupt changes is discovered, one thing is becoming crystal clear: Climate change policy today has become severely dated, and we need to catch up.

Just a few years ago, when the Kyoto Protocol was still a valid way of preventing dangerous climate change, emission reduction strategies were appropriate. We did not know nearly as much about abrupt climate change and abrupt impacts as we do today. The IPCC had not pronounced that greater than 100 percent emissions reductions for a sustained period are required to prevent dangerous climate change. (16) Now we know these things, and now we know we must begin to remove CO2 directly from our atmosphere because no amount of emissions reductions can remove greater than 100 percent of annual emissions.

We also know that once fully industrialized, air capture of CO2 can be done for $25 per ton. This means the removal of 50 ppm of CO2 from the atmosphere can be done for what the US paid for healthcare in 2005 ($2.1 trillion). (17)

Why are we not yet implementing these changes? A large part of the answer is that the perceived debate has masked the facts. Climate science is not real to most people. It doesn’t really affect many of us yet; it’s not a priority, so it is not reported. Humanity needs to be brought up to speed. Once the knowledge is spread around – as crucial scientific facts, not politics – we will make the correct decisions. One only hopes we can spread that crucial knowledge before abrupt changes begin.

Notes

1. We are using fossil fuels one million times faster than Mother Nature saved them for us . . . Richard Alley, Earth: The Operators’ Manual, Norton Publishing and PBS documentary.

2. 14,000 times faster… Zeebe and Caldeira, Close mass balance of long-term carbon fluxes from ice-core CO2 and ocean chemistry records, Nature Geoscience, Advance Online Publication, April 27, 2008.

3. 100 times faster than anytime in 65 million years . . . Diffenbaugh and Field, “Changes in Ecologically Critical Terrestrial Climate Conditions, Natural Systems in Changing Climates,” Science, Special Climate Edition, Volume 341, August 2, 2013, page 490, first paragraph: “The Pleistocene/Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) encompassed warming of 5 degrees C in less than 10,000 years, a rate of change that is 100-fold slower than that projected by RCP8.5.”

4. Abrupt climate change as fast as a few years. Abrupt Climate Change – Anticipating Surprises, National Research Council of the National Academies of Science, December 2013, Preface, page vii, second paragraph.

9 to 15 degrees across the globe . . . Alley, The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt Climate Change, and Our Future, Princeton University Press, 2000, page 119, Figure 12.2.

Data for figure 12.2 is from Cuffey and Clow, “Temperature, accumulation, and ice sheet elevation in central Greenland through the last deglacial Transition,” Journal of Geophysical Research, volume 102(C12), pp 26,383 to 26,396.

Greenland temperature change is twice that of the global average. Chylek and Lohmann, “Ratio of Greenland to global temperature change – comparison of observations and climate models,” Geophysical Research Letters, July 2005. Chylek and Lohmann say the Greenland temperature change is 2.2 times greater than the global average. From Alley’s Figure 12.2 (Cuffey and Clow), the 25 to 35 degree F abrupt changes in Greenland would equal 9 to 15 degrees average across the globe.

Also see: 25 to 35 degrees in “Greenland, National Research Council, Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises,” Committee on Abrupt Climate Change, 2002. Figure 2.5, page 37.

5. More extreme than previously understood. Abrupt Climate Change – Anticipating Surprises, National Research Council, preface, third paragraph.

6. Extinction of 72 percent of North American Mammals, ibid. page 1, second paragraph

8. West Antarctic Ice Sheet, ibid., pages 7, 13, 33, 34, 59, 61, 62, 150, 161.

9. Seventy-five percent of Caribbean reefs destroyed. Alvarez-Philip, Dulvey, et. al., “Flattening of Caribbean coral reefs: Region-wide decline in architectural complexity,” Proceedings of the Royal Society-B, June 2009.

10. “Polar Bears,” Abrupt Climate Change – Anticipating Surprises, National Research Council, page 118.

11. The American West has warmed 70 percent more than the global average. Hotter and Drier, “The West’s Changed Climate,” Rocky Mountain Climate Organization, 2008, Executive Summary, page iv, paragraph 1.

12. Spring is coming 30 days sooner in the American West; 10–30 days over the 1948–2000 period. I. Stewart, D. Cayan, and M. Dettinger, “Changes in snowmelt runoff timing in western North America under a ‘business as usual’ climate change scenario,” Climatic Change 62 (2004): 217-232. Page 223, 4. Results, second paragraph.

13. “Bark Beetle Outbreaks,” Abrupt Climate Change – Anticipating Surprises, National Research Council, page 21.

14. The Amazon has flipped from a carbon sink to a carbon source; Lewis et al., “The 2010 Amazon Drought,” Science, February 4, 2011.

15. 301 million trees killed in Texas in the drought of 2011; Texas A&M Forest Service.

16. IPCC 2013: Greater than 100 percent emissions reductions; IPCC 2013, Summary for Policy Makers, E.8 “Climate Stabilization, Climate Change Commitment andIrreversibility,” p 20, fourth bullet.

17. Lower Limit for Air Capture Costs: $25 per ton CO2 or slightly lower than the suggested minimum price for flue capture; Lackner et al., “The urgency of the development of CO2 capture from ambient air,” PNAS, August 14, 2012, page 13159, paragraph 6.