Significant Sunny Day Beach Erosion on South Padre Island, Beyond the King Tide

It’s still beautiful, but this is nowhere close to sustainable. It’s catastrophic, but it’s virtually unknown. The beach is nothing like in our past where sea level rise was not an issue. Most of the wilderness beach on almost all of Padre Island is almost completely washed away. Dunes are now actively eroding. Some places they are gone altogether leaving nothing but the back island to protect our shoreline. This is all being caused by sea level rise from ice sheet and glacier melt, and warming ocean water expansion, of a foot in the last century, much of which has happened in the last ten years; all by non-storm high tides, one little wave at a time. These waves just barely reach the foot of the dunes, but it doesn’t take much to wash away a little more sand with every wave.

It’s not subsidence. Subsidence does exist on Padre, it exists on all low slope barrier island that develop in sedimentary geology – which is almost all of them. Sediments compact over time. It’s not sand starvation from inland reservoirs either. In Texas for example, we quit building large reservoirs that trap sediment in 1969. Historically most of these low-slope barrier island beaches are relatively stable.

Beaches have an extraordinary ability to self-repair, but they can only do this with sea level rise of less than 5 to 10 mm per year. Once this threshold is crossed, they begin to erode and eventually disintegrate and sink beneath the waves.

Sea level rise has been accelerating and the true amount of acceleration is masked by the certainty of statistics in sea level trend measurement. It takes decades to develop valid statistics from data with such large variability as weather data or tide gauge data. But logically, we do not need statistical certainty to tell us what’s happening because we can simply look at the data ourselves on the internet. Bob Hall Pier, Port Isabel, Rockport are NOAA tide gauges that bracket Padre Island north and south. Mansfield Pass sits about in the middle of the island. Sea level rise int the last ten years at these gauges runs between almost five and almost six inches. That’s over 12 or 13 mm per year — more than the self-repair erosion threshold and far, far more than the 3 to 5 mm per year the long-term statistically certain trends speak of.

NOAA’s sea level rise trend at Port Isabel for example, is 4 mm per year. It’s based however on the entire record at Port Isabel from 1944 to 2018. Sure, the last ten years at Port Isabel at 0ver 12 mm per year may be influenced by natural variability. But what is the chance that it is not, when we have been warned for so long that sea level was scores of feet higher in prehistory at this temperature?

Persistent dune erosion from normal non-storm high tides on South Pare Island, 10 miles beyond the end of pavement on the four-wheel drive wilderness beach.

The science, and many of the scientists say we just can’t tell yet because of this natural variability thing. At the same time they tell us sea level is rising more rapidly, and the warmer it gets the faster it rises. They tell us that the last time it was as warm on Earth as it is today, sea level was 40 feet higher, and the last time it was about a degree C warmer than today it was 200 feet higher.

So what part of their story do we believe? This statistical certainty thing in climate science is not good. There is a concerted push among academic climate leaders to use more logic and expert judgement to help us more accurately understand what’s happening on Earth with these rapidly accelerating trends that are not statistically valid for decades or even human generations.

Most of us don’t have the resources to visit a four-wheel drive wilderness beach. We don’t see this happening. It happens very slowly. It’s insidious. Because it happens so slowly, it doesn’t get much attention. It’s just not visible to the public.

Most of us go to the beach at the condos, or the park where the beach has been nourished because it is such a high dollar amenity. The beaches most of us visit, where a beach still exists, are restored (nourished) by dredging up sand from offshore or some ship channel somewhere, and that sand is pumped onto those high-dollar beaches and smoothed out with bulldozers. Why most of us don’t see this happening is because it is done generally in the off season, logically.

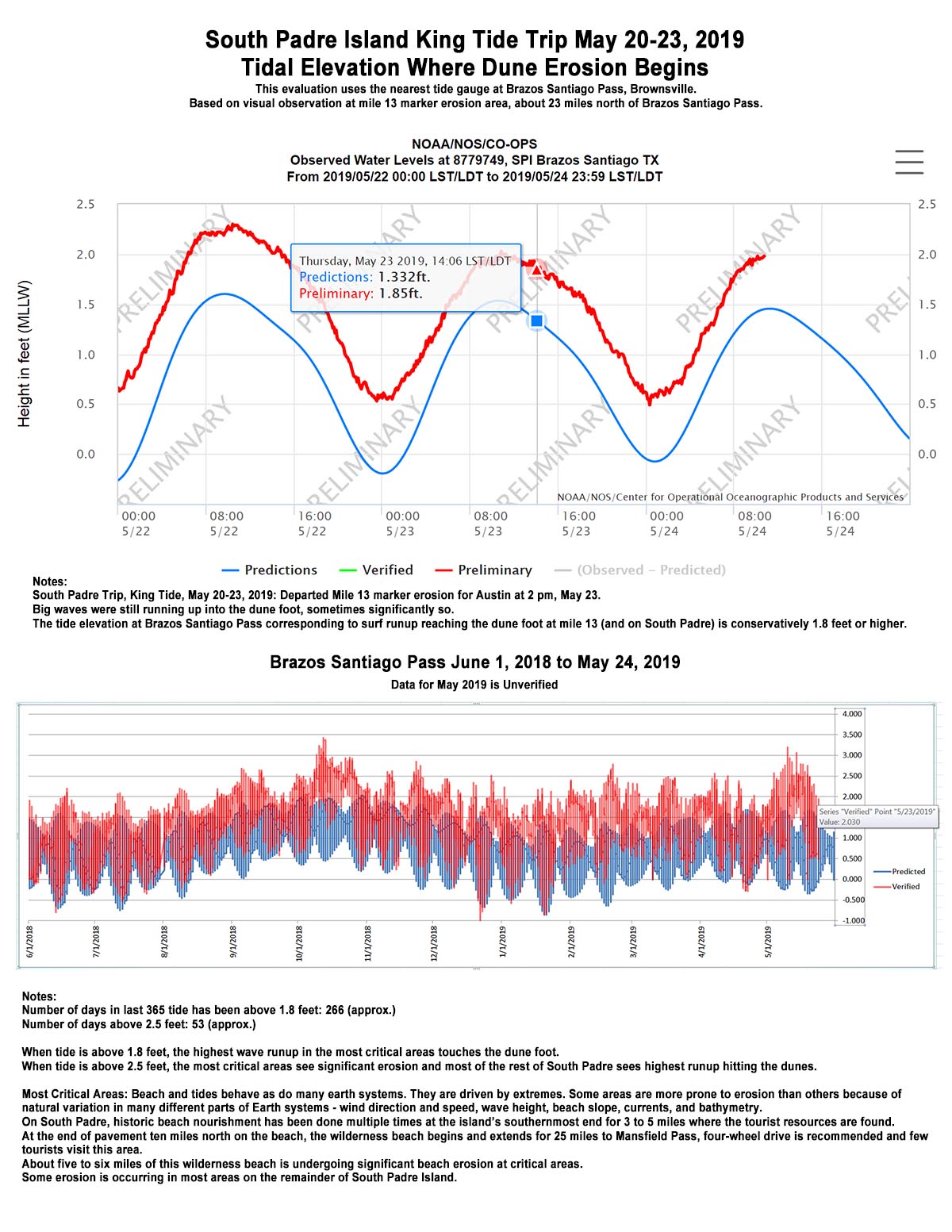

We don’t see the waves lapping up against the dunes because it happens on the wilderness beach, four-wheel drive only, or if not, you do get up one of these beaches chances are you really wish you had four-wheel drive. Those of us who do get up that four-wheel drive beach often don’t see it because the erosion happens only during the highest of high tides. On 53 days last year the highest of the high tides reached an elevation that created significant erosion. But the high tides only last for four to six hours during each of those 53 three days and half the time it’s dark. The rest of the time the tide is low (or lower,) and there’s a beach out in front of the dunes, just like normal, we think.

There was a big wind this trip to film the King Tide and sunny day beach erosion on South Padre Island. A gale warning was issued offshore with waves 11 to 14 feet. Wind-blown sand stung bare feet. Sand drift coated everything. The only way to get away from it was to stand below where the waves were running up, in the washup at times, and still the wind whipped up the wet sand from the water compacted beach. King Tides happen twice a year for 4 to 6 weeks in May and October, for five to seven days during each 13 or 14 day tide cycle where the sun and moon align just right to create the biggest high tides of the year.

The surf was way big this trip. Spray reduced visibility to two to three miles. The continuously crashing surf sounded like a freight train all night the first night, camped at mile 17 beyond the end of pavement on the wilderness four-wheel drive beach.

Evidence that the water had been up into the dunes was to be seen with fresh vertical sand faces where sandbergs had calved off and washed away after the toe of the dune was undercut by waves. By the second day out, the wind had layed to a normal 15 to 25 mph, the King Tide was full on and the bigger waves were up into the dunes eroding them a little more, and a little more with each wave. Sometimes three or four waves came in a big set and kept the water up on the foot of the dunes the whole time.

Normally, beaches self repair from erosion like after a hurricane. A hurricane will erode the dunes and pull much of that sand out into the Gulf near-shore zone, flattening the beach and making it wider. Over just a few months the beach profile begins to steepen back to normal as each wave moves sand particles shoreward from the near shore zone. After a few years, natural dune rebuilding is well underway as the sand moved ashore dries and blows. This natural self-repair is only viable with near-stable sea level though.

Low profile barrier island beaches across the world (like Padre), because of climate change caused sea level rise, are now no longer self-repairing because sea level rise has crossed the barrier island beach disintegration threshold.

South Padre Island looking south from 75 feet at about Mile 10 beyond the end of pavement on the four-wheel drive wilderness beach. Note the consistent angle of the big dune in middle-right of the photo. This angle is caused from the surf eroding the foot of the dune and sand sliding down into the surf and being washed away, like in the “sandberg” image below.

The US Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), Coastal Sensitivity to Sea Level Rise, A Focus on the Mid-Atlantic Region, 2009 presented critical information on the sea level rise rate contribution to beach erosion and how much sea level rise creates how much erosion. The wave-dominated low profile barrier islands on the Mid-Atlantic Coast are very similar to the Gulf Coast, so the information in this report can serve as a harbinger of things to come for our barrier islands here on the Third Coast too. Eleven years ago when this report was written however, impacts were not yet well developed. Today they are, they’re just hard to see because of where they are located.

What USGCRP said was that with the existing 3 to 4 mm per year sea level rise on the Mid-Atlantic Coast, coastal erosion, wetlands conversion to open water, and unrecoverable barrier island disintegration has already begun. Add 2 mm per year sea level rise to the existing rate and the area impacted becomes moderate. Norfolk, Virginia had a rise rate of 5.2 mm per year in 2018. (By 2100 this rise rate equals 20 to 24 inches of sea level rise.)

Add 7 mm per year to the existing rate and almost everywhere on the east coast sees widespread and significant coastal erosion, wetlands conversion to open water, and unrecoverable barrier island disintegration. (By 2100 this rate of sea level rise equals 39 to 43 inches.) The latest NOAA sea level rise report (Sweet 2017) says 8.5 feet by 2100 worst-case and you know, most things climate today are either worst-case or beyond. But they also say there’s another number that needs considered.

This is the 1% probability tide; or, the 100-year tide, like the 100-year storm and the 100-year flood that the insurance industry provides protection for. It’s not a storm tide, it’s just natural variation of tidal range, like natural variation of rainfall amounts. NOAA says the 100-year tide in 2100 is 13.1 feet above today’s sea level in Florida, and similar for most other highly populated areas of the US.

On the Gulf Coast, Church 2014 (cited in the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report) says 1950 to 2000 sea level rise was about 2.5 mm per year, about 0.5 mm less than what Church says was 3 mm per year on the East Coast. So the situation is quite similar between the USGCRP East Coast report and the Gulf Coast.

NOAA says sea level rise in Rockport on the Central Texas coast just north of Padre Island is 5.62 mm per year averaged from 1937 to 2018, and at Port Isabel near Brownsville at the very southern end of Padre Island is 4 mm per year averaged from 1944 to 2018. These are 75 to 80 year averages though and this averaging discounts recent increases that are obvious in the tide charts. (Rockport, Port Isabel)

Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) has produced a Sea Level Rise Report Card for 32 locations on the US Coast. They use a 36 year average so the recent increase in rate is not so skewed as NOAA’s above. VIMS says Rockport had a 6.8 mm sea level rise rate in 2018, partially from man-caused subsidence, and Port Isabel a 4.6 mm per year rise rate.

The bottom line is that sea level rise of 3 to 4 mm per year allows beach erosion and disappearance of wetlands to begin, and 5 to 10 mm per year causes barrier islands and coastal wetlands to disappear.

There is a threshold where where beach erosion and disintegration cross through a point of no return (unless global warming is reversed) where barrier island disintegration proceeds much more rapidly than in the past. USGRCP says this threshold is plausibly as low as 3 to 4 mm per year, and certainly at 5 to 10 mm of sea level rise per year. It’s important to note, that man-caused subsidence doesn’t matter, it’s total sea level rise from whatever reason that is collapsing our barrier islands.

In about 2013, Padre Island National Seashore began closing the beach on extreme high tide days for the first time ever during sunny day conditions. What likely happened is that increasing sea level has eroded sand from our beaches into the near-shore area over the last 20 years. This is evident in that beach width has been slowly declining in the Central and South Texas region since about the turn of the century. This process has removed the forebeach that protected the dunes.

The Bureau of Economic Geology Guide To Padre Island helps explain:

PADRE ISLAND NATIONAL SEASHORE – A GUIDE TO THE GEOLOGY, NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS, AND HISTORY OF A TEXAS BARRIER ISLAND, State of Texas, Bureau of Economic Geology, 1980, figure 74.

Increasing sea level removes sand from the swash zone where surf runs up the forebeach. This reduces the width of the backbeach. The back beach width determines how much wave energy is absorbed before any wave can reach the dunes. Because the forebeach area is mostly gone now, very little wave energy is dissipated before the waves reach the dunes.

What our wild beaches looked like in the past. Padre Island National Seashore, about mile 35 down the four-wheel drive beach, 2003.

Used to be, when we had King Tides the surf would spill over onto the backbeach area but never make it up to the dunes. Only tropical systems eroded dunes and these were few and far between allowing self restoration to take place. Now, two things have happened: sea level has risen three or four inches in the last generation, but more important the forebeach is gone. Now, every time the tide gets into King Tide range, it erodes a little bit into the dunes. Each little bit creates sandbergs that slowly eat away at the total mass of the dunes at a rate that is faster than the wind can rebuild them.

Sandbergs calve into the surf. Middle ground left, a sandberg is being eaten by the surf. Shorebreak has eroded the base of the dune away allowing a large block of sand to slide down into the forebeach area. The characteristic angle of repose is indicated in the next dune up the beach telling us a sandburg has calved there too, and been completely washed away. (2017, mile 13 beyond end of pavement on the wilderness four-wheel drive beach at South Padre)

Erosion is not consistent along the beach. Variations in bathymetry (underwater topography) cause currents to vary. Eddies set up in different places in different years. Some years winds blow from one direction more than another. Timing is important – what direction the wind is blowing when high tides occur makes a difference.

What results is that most of Padre Island is seeing dune erosion reach a second stage where the forebeach is mostly gone and dunes are being consistently attacked. Some of Padre is now entering a third stage where dunes are being completely eroded away. Next we get island breaching. Historically this only happens with tropical systems and the probabilities are that tropical systems will do the deed. But locally on Padre, if our lull in tropical system strikes continues, another five years will plausible see King Tides overwashing the island in the most critical places where the erosion rate is the highest.

Five or six miles of the 25 mile wilderness beach are now seeing significant dune erosion. One or two of those miles have seen the dunes completely washed away. The rest of the beach is seeing miner to moderate dune erosion, lean heavy on moderate.

This is how it begins. Wave runup on a healthy beach does not reach the dunes except during storm periods. This is happening a lot more than the press reports. At 1.8 feet of high tide, wave runup in the most critical areas touches the dune foot on South Padre. The number of days in last 365 that the high tide was above 1.8 feet on South Padre was 266 (approx.). When the tide reaches 2.5 feet, significant dune erosion is underway in the most critical areas and the biggest wave runup is reaching the foot of the dunes along most of the rest of South Padre. The number of days of high tide was above 2.5 feet in the last 365 was 53 (approx.)

The only way to stop it is to reverse the warming that caused it to begin. This warming level was crossed about the time the swash zone began to erode away the forebeach in about 2000. The global temperature then was about 0.5 C above preindustrial. To be safe, we need a safety factor so the safe limit of warming is about 0.25 C. We are at 1 C now, and best case emissions reductions allow the temperature to continue warming up to about 1.7 or 1.8 C before falling back to 1.5 C by 2100. This is unacceptable as it allows the sea level rise rate to continue increasing allowing our beaches to erode even faster than now.

It will not stop until we reverse warming and this is why carbon dioxide removal is so important. Without it, our beaches are doomed. Can our society live without beaches? When deeply considered, and understanding that the majority of global wealth and global infrastructure are located right at or very near sea level, the answer is stark.

What do we do? Certainly, if this was real and we all knew about it we would feel differently about climate change as a society. Seventy or eighty percent of us believe it’s real and it’s our fault, but we have yet to act because we still doubt; because we don’t see the damage or if we do it’s explained as “natural variation” by the Climate Change Counter Movement propaganda, or worse, by the vagaries of scientific certainty.

I fell into a partial explanation of why it is that this erosion phenomenon is not more widespread talking to a local this trip. Sure, Miami and Charleston get news when the tide rises into their streets, but where is the coverage of beach erosion on wilderness beaches?

This local was a fisherman who was on his way back to town from a favorite fishing spot at Mansfield Pass, a three or four hour trudge when the surf was running up into the dunes as it was when we talked. He was a lifelong resident and had never, ever seen the beach like this before, and he fished a lot. I see it because I plan these filming trips around the middle of King Tide season, but still, I miss a lot of good shooting because half the time it’s dark. The maximum high tide also only lasts for five or six hours. Too, five days a week are weekdays and not really available for beach recreational, and very few people go to a wilderness beach that is not nourished like almost all tourist beaches are where most people visit. And for most people, visiting a four-wheel drive wilderness beach is not an option because they do not have an appropriate vehicle. (And please, think twice about visiting a four-wheel drive wilderness beach in a town SUV. All four-wheel drives are not created equal. Most will not take kindly to conditions during extreme high tides.)

So what do we do? Talk about it. Make others aware. Each of us has a responsibility to help save the planet because we each know now what we have to do. We can make a difference.

Read another Beach Report from 2017 and tell your friends. Climate change is here, it’s bad, it will get much worse much faster from here on out if we continue to sit idly by, and it radically degrade the the way we live, not just our children.

Further reading on Padre and sea level:

PADRE ISLAND NATIONAL SEASHORE – A GUIDE TO THE GEOLOGY, NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS, AND HISTORY OF A TEXAS BARRIER ISLAND, State of Texas, Bureau of Economic Geology, 1980.

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/pais/1980-17/contents.htm

Climate Change Science Program 2009 Coastal Sensitivity to Sea Level Rise. Focus on the Mid-Atlantic Region (Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency) p 320

https://www.globalchange.gov/sites/globalchange/files/sap4-1-final-report-all.pdf

Church et al., Estimates of Regional Distribution of Sea Level Rise over the 1950 to 2000 Period, American Meteorological Society, July 1, 2004.

https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/1520-0442%282004%29017%3C2609%3AEOTRDO%3E2.0.CO%3B2